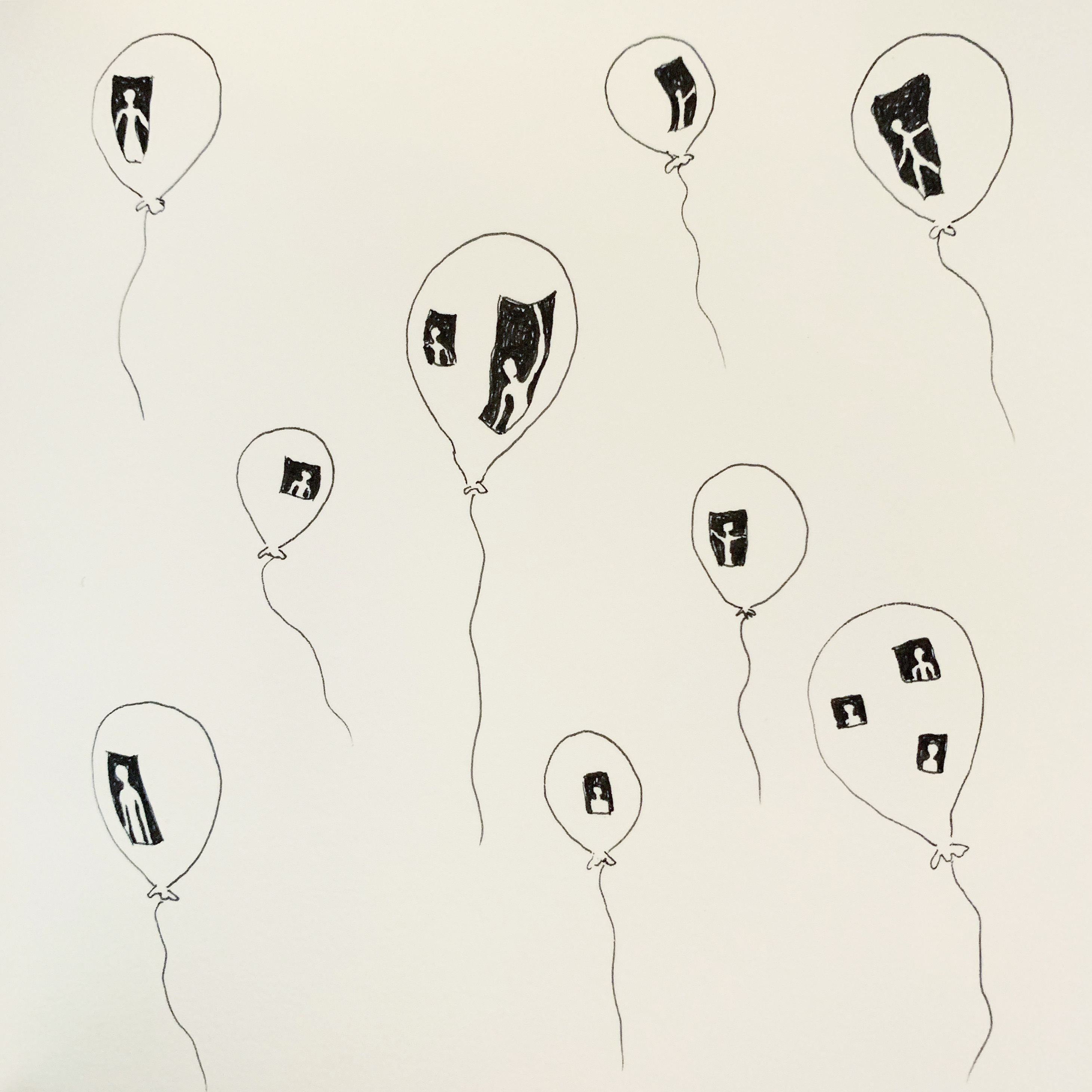

Artwork by Ise Henriques Sharp

Our misguided reluctance to ask sensitive questions, and why we should do it more

When you know a friend has recently heard bad news or has experienced a significant life event, we all have had the dilemma: Can I ask them about it? Would it just upset them? Am I a close enough friend to even ask? We worry about triggering our counterpart or coming across as too intrusive or too insensitive.

In the face of such questions, most people choose the safe option – to just keep quiet. Often, we assume that other friends are asking those questions. But, what if they are not? And by choosing to stay quiet, how does that affect our friend who is dealing with bad news or trauma?

I have thought about this a lot recently in light of my own experiences. In high school, I experienced a very traumatic health event that came on suddenly and without much explanation. Because of its mysterious nature, I was not equipped to fully discuss what had happened with my friends. And I found that many of my friends did not know how to ask – perhaps for the same reasons I highlighted above. And then, school started and homework beckoned, parties were held. People just forgot. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but I did find myself increasingly isolated; physically and psychologically recovering from these health events while many of my friends didn’t know any of the details.

The thing is, that sensitive question would have made all the difference not only in my feelings of isolation, but also in my psychological recovery. For me, the simple act of a question signaled interest and care that was critically important during a traumatic and confusing time. The people who did ask those questions had an outsize impact on my well-being.

This phenomenon actually has a name. In psychology, it is known as the “stress buffering hypothesis”. This theory proposes that social support weakens the physical and psychological toll of traumatic events on one’s health. In other words, social support can protect an individual from the negative consequences of stress on one’s health. Through this lens, that sensitive question could actually be very meaningful in supporting an individual.

So, these concerns about making a respondent feel badly or making ourselves look unfavorable – are they well-founded? Do they make sense? The podcast, “Freakonomics Radio” interviewed three researchers to answer that very question. In episode 451, “Can I Ask You a Ridiculously Personal Question?”, the host takes us through the research study of three professors at Wharton School of Business and George Mason University. They wanted to know: How reluctant are people to ask sensitive questions? And what are the reasons for this reluctance?

It turns out, they found that our concerns about asking that sensitive question are usually unfounded. They divided their study group into askers and responders, and the interactions were anonymous and online. In one round, askers had to ask five questions to the respondent, and were paid small amounts if they chose the sensitive questions. Responders knew that the askers picked the questions they asked. Even with the incentive, the askers did not maximize their payment and did not ask all sensitive questions – suggesting that they did not want to make the other person uncomfortable and still felt awkward despite the anonymous format and the cash reward.

In the next stage, responders were told that askers were randomly assigned the questions, and thus couldn’t choose whether to ask a sensitive question or not. However, in reality, the askers were again choosing the type of question to ask. In the end, askers chose a similar number of sensitive questions when the respondents couldn’t assign blame compared to when the respondents could assign blame. This result shows that the reluctance to ask sensitive questions persisted, even if the other person doesn’t view you unfavorably for asking it. Finally, when asked to rate how comfortable their counterpart was in answering the sensitive question, askers consistently overestimated the discomfort level. In fact, the responders were far more comfortable than the askers anticipated and were happy to answer the question.

Taken together, these results suggest that we have a strong aversion to asking those sensitive, personal questions due to worries of the impression we make and of causing discomfort. But, we also overestimate how uncomfortable our counterpart will actually feel in answering the question. So, our strong reluctance to ask questions might actually be misplaced!

In the last year, when we have all seen tremendous loss in our communities and in the world, and enormous upheaval to our lives, it is even more important to check in on each other and provide that social support. So, go forward and ask that question – ask about what actually happened or how they are actually feeling. Let’s be braver about asking those important and personal questions because they could really help someone. Chances are that our friend will not feel that uncomfortable and the potential effects of taking that step could be enormous.