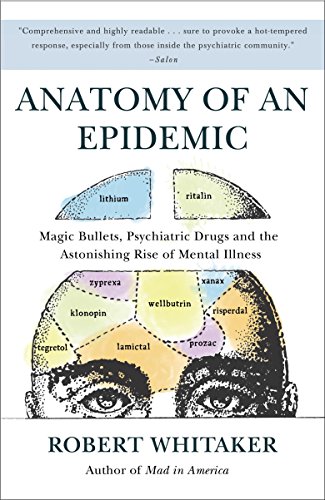

The book Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America written by Robert Whitaker criticizes the field of psychiatry and the increased use of psychiatric medication that has occurred in the past few decades. It presents bold questions and arguments related to this topic. Whitaker argues that psychiatric medication is responsible for the rise in mental illness rates seen in the U.S. While this book draws attention to many aspects of pharmacotherapy that are important for health professionals to question and consider, many of the claims posed in the text are one-sided, biased, and disregard the complexity of the etiology of mental illness. As a result younger readers seeking information about psychiatric medication must be warned about some of the pitfalls of Whitaker’s arguments.

In the first chapter, “A Modern Plague,” Whitaker claims that since the ratio of individuals receiving federal support for mental illness in 1955 was higher than that of individuals in state and country mental hospitals, the introduction of Thorazine, an antipsychotic medication, in 1954 was a catalyst for mental illness. However, a detrimental flaw in this argument comes from the fact that individuals can receive federal support in the form of Supplemental Security Income (SSI) or Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) at the same time.Therefore, by combining both of these numbers into one statistic, Whitaker is inflating the number of individuals receiving aid based on mental illness, as it is not uncommon for the same individual to be enrolled in both programs. By not considering this possibility, Whitaker is building biased claims on faulty evidence.

Whittaker then proceeds to compare rates of SSI and SSDI across years, showing its rise. While comparing the same measure does eliminate some of the discrepancies found when comparing hospitalization rates with those receiving financial support for mental illness, the general argument Whittaker poses is still a biased one that disregards the impact of countless other variables. For example, Whitaker fails to consider that the approval process to receive SSI and SSDI is not very restrictive. According to Dr. E. Fuller Torrey, a research psychiatrist specializing in schizophrenia and the founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center, “most people who apply [for SSI and SSDI] are ultimately approved if they persist through the appeal process.” While the Reagan administration attempted to remove these benefits from individuals who did not qualify and make the distribution more restrictive, they were ultimately unsuccessful. Instead, public knowledge regarding SSI and SDI assistance rose. The surge in individuals applying for this service has also been facilitated by the advertising of these programs on billboards in areas with high poverty rates and an increase in the number of social workers focused on assisting individuals with the application process. Taking this into consideration, it becomes more apparent that there are alternate explanations and factors that should be considered when determining why the surge in SSI and SSDI rates occurred apart from the introduction of Thorazine.

Throughout the rest of his book, Whitaker continues to critique many aspects and theories of psychiatry, further supporting his claims with biased, one-sided, and faulty evidence. However, embedded within Whitaker’s critique of the theory of chemical imbalance and the field of psychiatry at large, we see a hidden kernel of truth. Whitaker writes, “the chemical imbalance theory of mental disorders… was embraced by psychiatrists because it ‘set the stage’ for them to become ‘real doctors.’ Doctors in internal medicine had their antibiotics, and now psychiatrists could have their ‘anti-disease’ pill too” (Whitaker, p. 78). This sentence serves as a reminder that the field of psychiatry has unique challenges that differentiate it from other medical fields, and while there are neurological factors at play, there are also a myriad of environmental factors that are also involved. These interact and influence each other in a way that is unique to each individual. Given this complexity, it is understandable that one medication or treatment may not work for everyone and a combination treatment that includes psychotherapy is most beneficial for individuals. Whitaker’s critique, while very extreme, remind us of this.

All in all, Whitaker’s critique remains one-sided and biased and discredits a lot of progress made in the treatment of mental disorders and the helpfulness of psychiatric medication. I still believe that there is something that can be learned from Whitaker’s text. It reminds psychiatrists of the large variation within patients and patients’ responses to psychiatric medication, the possible side effects and unwanted consequences that can arise from prescribing a medication that is not the ‘right fit,’ and the importance of a holistic treatment approach encompassing a wide range of methods including psychological treatments. This encourages psychiatrists to prescribe medications with extreme caution and be extremely vigilant of their patients’ reactions to these medications during the first few weeks of consumption to determine their effectiveness. Additionally, it can help remind psychiatrists that pharmacotherapy is not a permanent solution to most mental disorders. Instead, it can act as a crutch to allow patients to reach a state in which their symptoms are regulated enough to allow other treatment approaches, such as psychotherapy, to be effective. Having said this, this belief is based on the fact that these individuals have prior knowledge about these medications and have already been exposed to the other side of the argument. For individuals without prior knowledge about psychiatry, the narrow-minded claims presented in this book can be misleading and alarming, which could cause patients to be more reluctant to take psychiatric medication that they could potentially benefit from. While there are risks to taking psychiatric medications and it is always important to consider these risks, it is also imperative that we consider the potential benefits. By painting a one-sided and dark picture of the field of psychiatry as a whole, Whitaker is facilitating a biased perspective that could impact individuals’ health-related decisions for themselves and their children that may be harmful in the long term.

References

Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S. L., Andersson, G., Beekman, A. T., & Reynolds, C. F. (2014). Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20089

Fuller Torrey, E. (n.d.). Anatomy of a Non–Epidemic – a Review by Dr. Torrey [Treatment Advocacy Center]. https://www.treatmentadvocacycenter.org/component/content/article/2085-anatomy-of-a-non-epidemic-a-review-by-dr-torrey

Kaufman, S. (2018). No, we do not want to bring back asylums (but we never “really” got rid of them). Project LETS. https://projectlets.org/blog/asylums

Vasile, C. (2020). CBT and medication in depression (Review). Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2020.9014