On March 13th, 2020, my college announced that we were expected to vacate our on-campus residences and return home for an indefinite period of time, following the outbreak of the novel coronavirus. While I was devastated, I was also convinced that I would be back by the summer, or at the very latest in time for my fall semester. There was no way I could have predicted that the global pandemic would persist and prevent me from returning to the safe haven I had spent nearly 2 years building for 18 long months, or 3 semesters of my precious 8. Perhaps part of me didn’t want to consider that possibility, given that my mental health, at the time, was already teetering on the brink of last resort, and I was acutely aware of the fact that returning home abruptly would further send it into a nosedive.

In the time between my eviction from college and when I finally decided to seek help for my rapidly deteriorating mental health, I found myself in the most harrowing depressive episode I have ever experienced, at a rock bottom I didn’t know existed. My relationships with the people around me, with food and my body, and even with myself in the larger sense, were deeply affected, and I found myself cornered by my own mind, unable to find a way out of the ruinous labyrinth I was building around myself. It took me 11 months of continual, chronic lows to recognize that I needed therapy, and it will likely take me years to overcome what I let fester in the period I neglected to act on what I should have known was a manifestation of my mental illness.

Admittedly, therapy has been transformative for my mental health, and for the first time in what seems like forever, I feel myself slowly getting better. I am armed with the ability to build myself back up after encountering setbacks, and the chronic lows are slowly fading into a dull pain in the back of my chest. I firmly believe, however, that I am still years away from recovery, if ever I am able to reach a point where I am unencumbered by the mental illnesses that bind me to the confines of my own mind. The reason for this, I have recently recognized, is the pervasive, negative effect of the male gaze, which to a certain extent governs how much I can recover, how much I allow myself to recover even.

This awareness came from a game of Truth or Dare, played in jest and good fun between a group of my high school friends, when a boy in the circle unwittingly made a disrespectful remark about the singer Lizzo’s body. I felt my eyes go wide at that time, and I shot him a nervous glance. I knew Lizzo wasn’t going to hear what he had to say about her body, and given her position on body normativity – which focuses on how the body feels and what it can do, rather than simply how it looks – it was unlikely that she would care about something an irrelevant onlooker had to say. What sent me into a spiral, however, was the realization that a comment made on a woman’s body was likely to affect every woman hearing it in some way, even if the body being commented on was not hers. In that moment, I was keenly aware and suddenly conscious of what my body looked like as I sat, relaxed and unposed, on the windowsill. I felt watched every time I reached for a sip of my drink, and I found myself shying away from the snacks, afraid that I was being observed, wondering what was going on in the heads of the people around me. It wasn’t my body that had been spoken of disrespectfully in that moment, but it was my eating disorder which was triggered. I sat with the thought of why this had affected me so much even weeks after that Truth or Dare game. I contemplated the patriarchal ideals which dictate what a woman’s “ideal” body should look like. I looked up articles about Lizzo and body positivity, negativity, neutrality. Eventually, I came to the conclusion that as much as I wanted to live to see the day we would abolish the standards which govern what women “should” look like, I likely would never be rid of the nagging voice in my brain that Margaret Atwood described as the “ever-present watcher peering through the keyhole in [my] own head.”

Upon further thought, I began to realize that many facets of my recovery were in some way tied to the male gaze, and how I would be perceived. In the throes of my depression, during my summer back home, I found myself in a toxic relationship that fell apart as quickly as it had started. For months after it was over, I endured a back and forth with the other person which left me exhausted, afraid, and intensely unhappy. Yet, it was not until I started therapy and mustered up some courage that I could actually tell my friends the truth about it. Every time I provided them with a detail of something that had triggered me, or in some way contributed to my plethora of mental illnesses, I found myself nervously asking, “Do you believe me?”

Growing up in India, I had been fed horror stories of how women are never believed. How if something ever happened to me, no one would take my word for it, because I was a woman. Even when I moved to the United States for college, and found myself in a far more liberal environment, I knew that a case had to be made for a woman to be trusted. It wasn’t until I identified a pattern of imposter syndrome in my thoughts, however, that I realized how much I had internalized the notion. It took the conscious acceptance of my inability to trust my own feelings as valid, in spite of my very real experiences, and a recognition of enduring self-doubt to confront how deeply the patriarchy was ingrained in my mind. It wasn’t until I had been through months of an emotionally traumatic relationship, without saying a word to even my family, that I understood how tightly the male gaze gripped the reins of my recovery. How could I recover from something I didn’t believe I had, something I was sure no one else would believe I had? To gaslight me and make me believe I was at fault, I was the villain, I was crazy, was so easy, and I was so sure that that was what other people would see too.- How, then, could I recover, when it wasn’t even a luxury or belief I afforded myself?

The male gaze is toxic not only for people who identify as female, but everyone that is in some way entangled with the patriarchy. While this details my specific, personal experience and understanding of the intersection between the male gaze and my recovery, I am aware that recovery is both possible and not necessarily as explicitly entrenched in the male gaze as perhaps I am concluding. I do think, however, that it is the very nature of the patriarchy that makes it so difficult to identify where recovery is concerned: the male gaze permeates so many areas of our lives without us realizing it, and it is so deeply normalized, that our mindsets are attuned to accommodate for it. The question that plagues me as I come to terms with the “ever-present watcher” in my head, then, is how can we educate ourselves about this, and dismantle it? And, more worryingly, if we are unable to, will I ever recover?

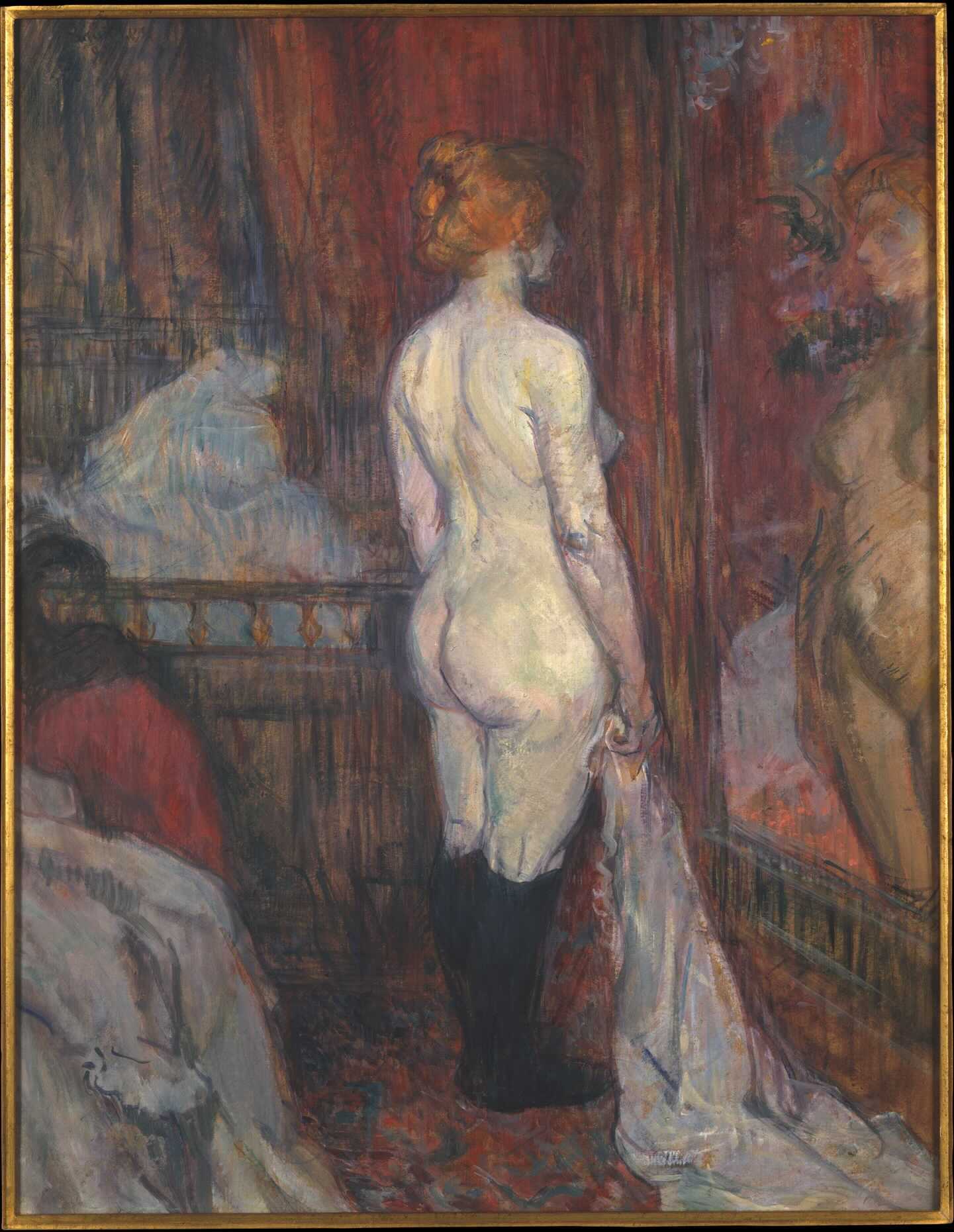

Cover Image: “Woman before a Mirror” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec